Written by Betty Escher

When you picture a museum, you probably think of glass cases and neat little labels. But in the Solomon Islands, it can mean something quite different. My favorite one wasn’t in some big building at all. It was in Barney Paulsen’s backyard.

We’d anchored off a small coastal village on Munda, New Georgia, not far from Guadalcanal, where the Battle of Alligator Creek raged during World War II. I’d read about it prior to our visit, but standing there amidst the jungle, history seemed to step out of the textbook.

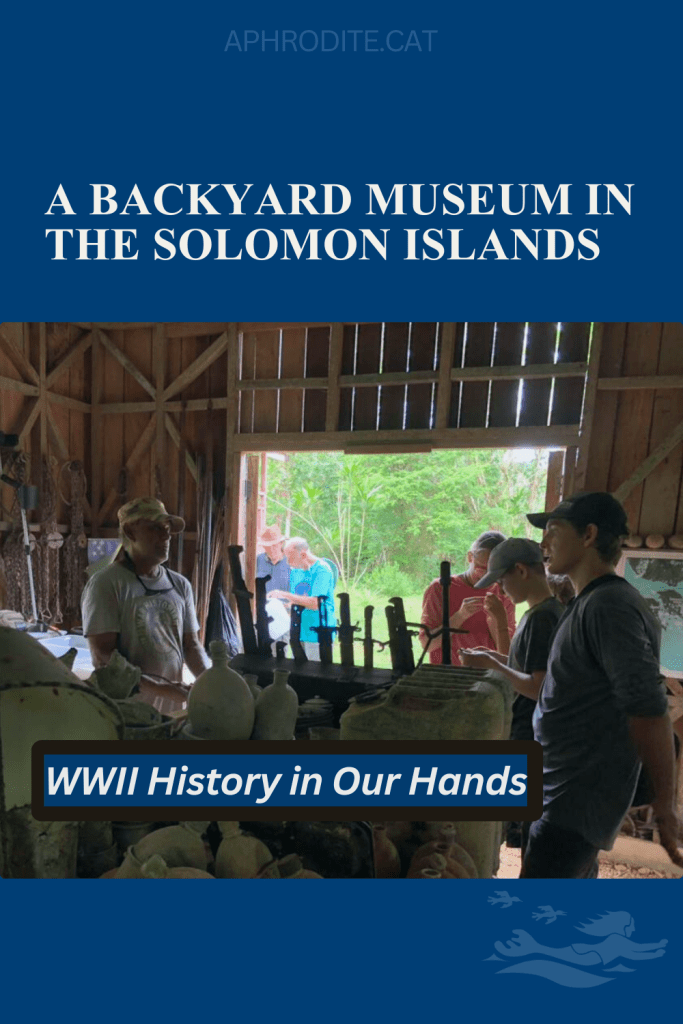

After a trek through the village, we were guided to the house of the man who ran the Peter Joseph Museum, Barney Paulsen. He led us to an old wooden shed with metal plane parts piled in front. Opening the door, we could see lines of items, the shed filled nearly to overflowing with bits of history.

He told us that most of it had been found just beyond his backyard or brought in by fellow villagers. Some of the items still had mud on them. Bullet-riddled helmets hung haphazardly over rusted machine guns leaning up against the wall.

“History seemed to step out of the textbook.”

– Betty Escher

Paulsen showed us a binder and a large container of dog tags. He explained that since founding the museum he had catalogued each dog tag, researching what had happened to their owners. Every page of the binder was dedicated to a different World War II soldier, listing relatives and their fate. Some, it seemed, had not died during the war, but instead lost their dog tags and gone on back home to marry and live out their lives.

Unlike bigger museums, the ones in the Solomons don’t hide rough edges. You can see how the tropics have begun to reclaim everything. The old glass bottles are fogged, the metal eaten away by salt, and that’s exactly what makes them feel so real. You’re not separated from history by glass and ropes. Now, you’re standing right in it, and in the same place it all happened.

History Still Lives Here

What amazed me most was how much of that history still lives on in local daily life. Kids fish near old wrecks. Families use parts of planes or tanks as fences and benches. And more morbidly, islanders are sometimes injured or killed by unretrieved land mines. One example had happened just before we arrived in Honiara when someone lit a barbecue on munitions from World War II.

There’s something deeply moving here, seeing how people have adapted their daily lives to incorporate their past. And furthermore, there is a tangible sense of local pride. Meeting villagers across the islands, many excitedly offered up stories of fathers’ and grandfathers’ efforts as scouts and spies aiding the war effort.

The Hero of Alligator Creek

One particularly heroic story came in the form of Jacob C. Vouza, a local islander who had volunteered his services to the U.S. forces stationed at the Henderson Airfield. On a trip to bring an American flag souvenir to a nearby village, he was captured by Japanese forces who found the flag and mercilessly tortured him for information.

Refusing to speak, his throat was cut, and he was left for dead. However, he regained consciousness, and upon doing so bit through his restraints and staggered three miles back to base to warn the Americans of the Japanese intent to invade across Alligator Creek — a warning which ultimately helped the Americans win one of the most impactful victories of World War II.

This blog post was written by Betty Escher.

Pin it

If you enjoyed this story, you can save it to your own Pinterest board using the image below. Thanks for reading and following our journey.

What an enjoyable read! I have a new friend who lives in the Solomon Islands and I was happy to learn more about the history of their occupation. I love the saying about history, “to go forward, we must go back.” Keep writing more, I just love reading about your adventures!

LikeLike